Architect Harry Weese designed the Washington Metro Stations, like Metro Center here, which he described in a Washington Post article in 1977 as having a “cathedral-like quality” for a monumental city. | Carolyn M. Proctor

You may have heard that there’s about to be a lot of commercial real estate opportunity here in D.C. At least that’s one optimistic way to describe the General Services Administration’s plan to offload as many federal buildings as possible — some to be redeveloped, some emptied and some sold.

The J. Edgar Hoover Building. The James V. Forrestal Building. The Robert C. Weaver Federal Building. What stands out about many of these massive buildings that the Trump administration now wants to dispose of is their architectural style: Brutalism. The style is an extension of the Modernist movement popular in the mid-20th Century and is best known for its minimalist designs, exposed concrete and deeply recessed windows. The name comes from the French phrase “béton brut,” meaning raw concrete.

Brutalist design, which flourished here in the 1960s and ’70s, is in the White House’s crosshairs. President Donald Trump has voiced his dislike on several occasions, going so far as to issue two executive orders — one late in his first term and one on the very first day of his second term — directing the GSA to “respect regional, traditional and classical architectural heritage in order to uplift and beautify public spaces and ennoble the United States and our system of self-government.”

The focus of Trump’s ire is often the Hoover building, home to the FBI (at least for now).

“It’s one of the Brutalist-type buildings, you know, Brutalist architecture. Honestly, I think it’s one of the ugliest buildings in the city,” he reportedly said in 2018 to an Axios source, calling the FBI building itself “terrible” and needing a “total revamp.”

But is it really that bad? Brutalism in D.C., the subject of a current National Building Museum exhibit, isn’t restricted to goliath federal buildings. It’s everywhere, from museums to the Metro system. Like any architectural style, there are stunning examples of it, and stunningly awful examples, too.

We asked architects in the region what they really thought about Brutalism, which D.C. structures they liked, and what should be done with those on the chopping block. Of the nine who responded, even those expressing a personal dislike of the style — like Chris Landis, co-founder and chairman of Landis Architects and Builders — still wanted to see at least some examples preserved.

Mixed reviews

Landis, who served on the Historic Preservation Review Board for two years, said he’s not a fan of Brutalism, noting many of the buildings today are in need of serious updates, for example to increase energy-efficiency.

“I think it would be a case by case situation,” he said of which buildings should be preserved and which replaced. “Sometimes, by preserving it, it will become a sort of a dinosaur and not be able to be used that much.”

Alana Lopez, principal and studio director at OTJ Architects, said that while the best examples of these buildings “maximize the aesthetic value of unadorned raw concrete” through their geometric design, sometimes they fail to relate to the human scale.

“However, I believe architects alongside owners can and should both preserve and reimagine these buildings,” she said. “The beauty of Brutalism is its predictability and exposedness so that with creativity and interventions such as recladding, seemingly outdated structures can be made relevant for the 21st century.”

New homes on the block

Speaking of housing, our architects suggested, in several cases, multifamily conversions for D.C.’s Brutalist buildings, though Landis pointed out it may not always be feasible, depending on a building’s floor plate and other factors.

“Repurposing potentially vacant federal office buildings as housing seems like the obvious new use for many of these Brutalist buildings,” especially in light of the current housing crisis, said Ben Kasdan, a principal with KTGY. He liked the idea of adapting the Weaver building at 451 Seventh St. SW in L’Enfant Plaza, home to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, where the street-facing concrete skin remains but the building center is opened up to more natural light.

That is the vision of Los Angeles-based architecture firm Brooks + Scarpa, as seen in the ”Capital Brutalism” exhibit at the National Building Museum.

OTJ, meanwhile, recently studied the “potential of reimagining 950 L’Enfant Plaza from office space to a multifamily development complete with a retail base,” Lopez said. The study concluded the property would work well as residential, “thanks to its desirable siting, favorable elevator/core location, and rectangular floorplate complete with fenestration on all sides of the structure.’

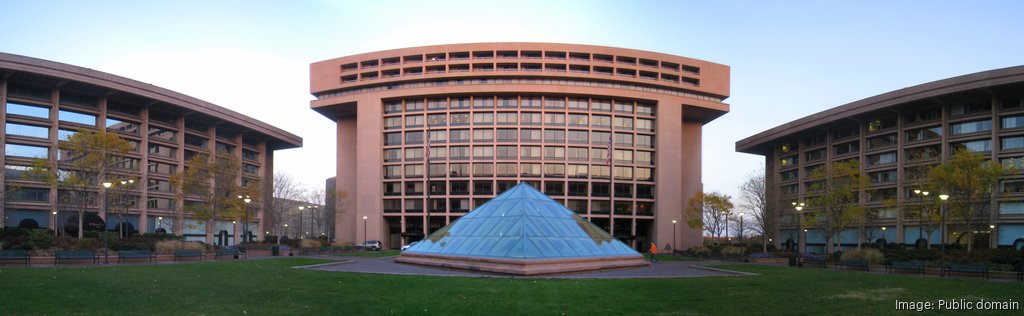

L’Enfant Plaza in Southwest Washington has multiple examples of Brutalist architecture. | Daderot / Wikimedia Commons

“Brutalist buildings, with their rhythmic and consistent structural bays, ample daylight, and slender floorplates, often make great candidates for conversion from one use to another,” Lopez said.

Taking the opposite tack, Robert Holzbach, principal and director of commercial office for Hickok Cole, said Brutalist buildings can pose challenges for adaptive reuse, “because their façade and structure are sometimes integrated,” making it harder to replace only a few components. The low floor-to-floor heights and deep floor plates, along with less natural lighting and often thick waffle-slab floors, can turn a conversion into a feat of engineering and creativity.

“This inherent rigidity and inefficiency can limit their flexibility in today’s real estate market, rendering some buildings candidates for replacement or repositioning rather than reuse,” Holzbach said.

Forward thinking

But that’s no reason to give up.

Gene Weissman, vice president of Architecture Inc., said his firm has renovated several Brutalist structures, including the East Building of L’Enfant Plaza, which was converted to a mixed-use property combining office and a hotel, part of the Hilton National Mall project. He’d like to see more renovations in that area, and the infusion of street-level retail, to bring it to life.

Shalom Baranes, principal of Shalom Baranes Associates, was even more protective of the polarizing architectural style.

“Advocating for the demolition of major structures on the basis of stylistic preferences strikes me as callously irresponsible,” Baranes said.

Indeed, Baranes argued in favor of renovation as a more environmentally responsible solution to the Brutalism challenge.

“They are in fact in better condition,” he said, “than many of the Neo-Classical early 20th Century office buildings we routinely lavishly renovate.”

Pick your favorites

“I think preservation plays an important role in defining cultural, political, and technological moments in our history. Identifying key examples for preservation is an important method to catalog these moments, just as a museum catalogs its works,” said Gene Weissman, vice president of Architecture Inc.

In that spirit, here’s a sample of the structures our architects chose as the best examples of Brutalism in D.C.

The open center of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden | Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, 1978

The Hirshhorn Museum

- Architect: Gordon Bunshaft

- Built: 1974

“The design is an open cylinder raised up on four legs, allowing people, views and breezes to flow under the structure. The clear and strong diagram of the building, with galleries circling the open courtyard, is reinforced by the detailing of the exposed concrete cladding. While this building is Brutalist, it feels dynamic and light with its use of space.” — Roger Schwabacher, HOK

The Metro rail stations in D.C., like Farragut North, are a version of Brutalist with their vaulted concrete. | Abdullah Konte / WBJ

The Washington Metro

- Architect: Harry Weese & Associates

- Built: 1976

“I find the Metro system’s stations one of the most unique examples of Brutalist architecture in D.C., as it conquered brutalism’s biggest critiques – its unforgiving and often uncomfortable form. By utilizing this style of architecture for tunnels and below-grade transit stations, the so-called cold forms of concrete and rigid geometries suit the function and use of the Metro perfectly and even serve to gracefully soften and lighten what is essentially a dank, dark tunnel.” — Gene Weissman, Architecture Inc.

“The iconic vaulted transit halls from the original D.C. Metro Stations, designed by architect Harry Weese from 1976, are my favorite example of Brutalist D.C. architecture. The consistent architectural language throughout the D.C. underground creates a uniquely unified experience for riders that evokes feelings of importance, efficiency, grandeur, and optimism about the future, befitting of the ideals that define our nation’s Capital.” — Ben Kasdan, KTGY

…and a controversial pick:

The FBI Headquarters on 9th and Pennsylvania Avenues NW has been targeted for redevelopment for many years now. | Joanne S. Lawton

The J. Edgar Hoover Building

- Architect: C.F. Murphy Associates

- Built: 1974

“While it is often criticized for its fortress-like appearance and the void it creates in the otherwise vibrant Penn Quarter, I find it architecturally compelling. The building’s interlocked massing, overhangs, and concrete forms create a powerful visual statement.” — Robert Holzbach, Hickok Cole

…and one with a suggested renovation:

The Robert C. Weaver Federal Building at 451 Seventh St. SW. Los Angeles firm Brooks + Scarpa designed a hypothetical adaptive reuse of the Weaver Building, featured in the National Building Museum’s “Capital Brutalism” exhibit. The design kept the street-facing Brutalist exterior skin while opening up the center of the building to natural light. | U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

Robert C. Weaver Federal Building

- Architect: Marcel Breuer & Associates, et. Al.

- Built: 1968

“The building is both muscular and sculptural. I believe the landscape could be more layered and planted to create outdoor spaces that would activate the ground plane. I would reimagine this building as a student think tank and internship center where our country’s best and brightest come together for a year to live and share ideas in the heart of the nation’s capital.” — David Jameson, David Jameson Architect

By the numbers

55% of nonresidential U.S. building stock was built between 1960 and 1980, comprising about 36 billion square feet.

242 — That’s the number of office buildings built in D.C. between 1959 and 1970. To put another way, office space increased by four times, from 5.75 million square feet to 27.4 million square feet in that time period, when Brutalism abounded.

Source: “Obsolescence and Renewal: Transformation of Post-War Concrete Buildings,” the master’s in architecture and master’s in historic preservation thesis by Kara Johnston, project manager at JLK Architects