2020 has delivered a series of events that have surfaced long-standing inequities within our society and communities. The confluence of COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, increased climate related events such as wildfires and hurricanes has shown that marginalized communities, especially those of color, have been for a long time subject to a life of increased stress, risk and early death.

While this year has been challenging, testing our resilience and our capacity to adapt, it has also provided an opportunity for introspection at the individual and community level of how we, through our actions and inhabitation of our habitats, have impacted the inequities in the places we live, work and play.

As a practicing planner and urban designer in a multi-disciplinary firm, the events of this past year have intensified my resolve to participate in a more equitable world in all aspects of my life. What does this mean? For me, it involves examining and including in my work an “Equity Lens” approach. The Equity Lens approach, as described by the 2019 American Planning Association (APA) publication: Planning for Equity Policy Guide, is a holistic approach that “challenges…practices and actions that disproportionately impact and stymie the progress of certain segments of the population.” This approach acknowledges the historical context of the inequitable policies and framework we’ve inherited and offers guidance on focus areas where we can challenge ourselves to learn from the mistakes of our past and work to correct them to ensure the future is more equitable and inclusive for all people.

For context, this approach uses the following definition of equity: “just and fair inclusion into a society in which all can participate, prosper and reach their full potential. Unlocking the promise of the nation by unleashing the promise in us all.”

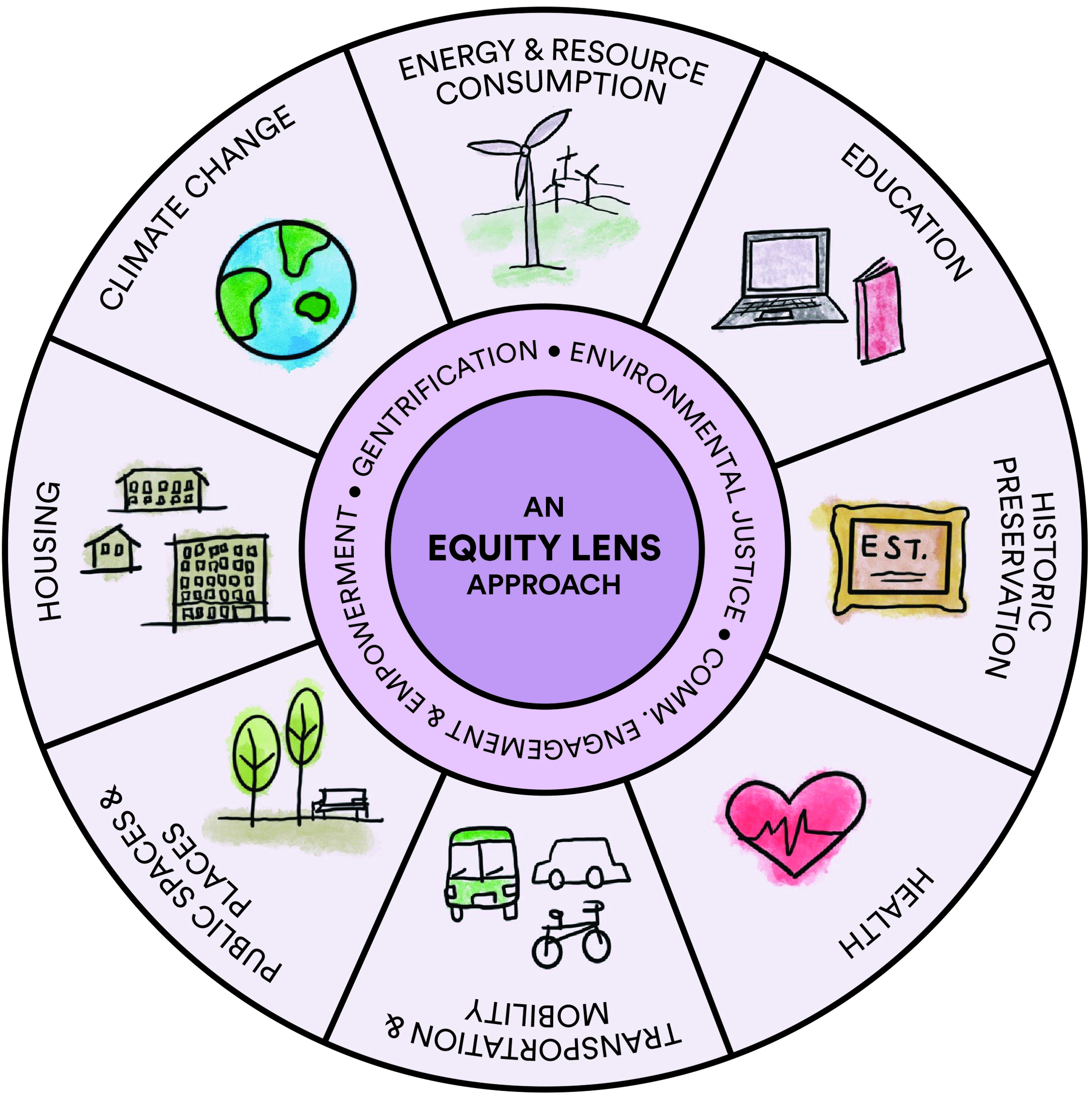

Within the framework of the Equity Lens approach are eight practice focus areas and three cross-cutting issues that apply to the eight areas. The eight practice areas are: (1) climate change and resilience; (2) education (the physical location of schools); (3) energy and resource consumption; (4) health equity; (5) heritage preservation; (6) housing; (7) mobility and transportation; and (8) public spaces and places. While the policy guide document offers several key measures in each practice area for consideration, in respect to planning policy work that may take years to achieve, there are also questions and suggestions brought forward that are tangible to address and achieve in the immediate future.

For example, within the Housing focus area, there is a call to promote an increasingly diverse housing stock, remove regulatory barriers, and focus on goals around affordability and combating displacement. In California, where there has been an ongoing housing crisis, state legislation has focused on increasing housing supply and streamlining processes to ensure implementation. Within this context, I’ve had the opportunity to work with colleagues across disciplines and clients and community stakeholders to get creative to address housing affordability, accessibility (universal design), and longevity and sustainability of the structures. Each new development brings different levels of challenges in respect to equity but also offers opportunities to be innovative and set a new and better precedent, and to learn how to do better next time.

More important than the eight practice focus areas are the three cross-cutting issues in the Equity Lens approach: (1) gentrification; (2) environmental justice; and (3) community engagement and empowerment. Gentrification is defined as a process that often results in the displacement of existing residents and cultural change of the area or community. It is often associated with the actions of development and revitalization. The APA emphasizes, one is a process while the others are actions, and states, “it is important to acknowledge that revitalization executed in the absence of an equity lens can result in the negative impacts of gentrification and is a contributing factor to the rising inequality in the nation’s metropolitan areas.” Environmental Justice is defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” Community engagement and empowerment is meaningful public outreach to all populations that allows all people to have a voice and access to decision

making. All these issues center on people.

These focus areas and cross-cutting issues on their own warrant deep exploration and understanding. However, when packaged together in this equity framework, they convey the complexity and intersectionality that comes with doing equitable work that emphasizes the need for transdisciplinary efforts fostered in collaboration and support.

With delving into this Equity Lens approach came reflection of my past and current work and life experiences onto the habitat I inhabit (the impact of my actions from the nucleus home, to the local community, regional area, state, national and global levels within the context of societal and physical environments). Through this process, it struck me that: equitable planning and design recognizes and incorporates the human experience with sound data and research. For much of the 20th century, development decisions focused largely on scientific data at the expense of the human experience.

This can be applied to all eight focus areas and address the three cross-cutting issues proposed in the Equity Lens approach. This will involve mindful listening and sometimes tough conversations; but I believe it can be done and it will be worth it.

In fact, it has already been done. Hope SF in San Francisco, California is an example of a new community created with the components of the Equity Lens approach. Hope SF is a crosssector initiative currently transforming four of San Francisco’s public housing sites into three neighborhoods with a mix of housing, retail and office, community services and facilities. It is unique from other new developments as it is a program focused on community development and reparations for its original public housing residents. The creation of these three neighborhoods has four goals and eight guiding principles that speak to the three cross-cutting issues of the Equity Lens

approach (gentrification, environmental justice, community engagement and empowerment). The four goals are: (1) Build racially and economically inclusive neighborhoods; (2) Recognize the power of residents to lead their communities; (3) Increase economic and educational advancement; and (4) Create healthy communities. To date, more than 750 new affordable homes have been completed with approximately 500 of these homes replacing public housing homes. Residents have participated in a Leadership Academy to help them build leadership skills and learn about the development process for more meaningful participation and onsite city-synced wellness centers across the four sites in the three neighborhoods have opened for residents. Hope SF is estimated to be complete in 2035 with the completion of 5,300 new homes across all income levels.

2020 has delivered a series of events that have surfaced long-standing inequities within our society and communities. It has been a challenging year but has offered me the opportunity to reflect and challenge myself to do better as a citizen planner. Getting re-acquainted with the Equity Lens approach this year offers a path forward to creating better and more equitable design; one that is focused on people and driven by data.

The components and cross cutting issues of the Equity Lens Approach by the American Planning Association. Diagram: Cindy Ma