The Essential

Repeatable Housing for the Unhoused

Homelessness in the United States

With over half a million people in the United States experiencing homelessness, the growth of this population outpaces the new supportive housing units being built to serve them. America’s homelessness crisis has been deteriorating over the last few decades but saw a dramatic worsening through the pandemic. Patterns of regulation in communities across the country have led to a lack of affordable housing, causing a boom in people experiencing homelessness. Fearing declines in home values despite evidence to the contrary, neighborhood groups pressure their elected officials to veto new affordable housing developments. When new projects do successfully circumvent NIMBY red tape, often zoning restrictions still reduce the number of housing units provided and individuals served.

So how did we get here?

The Housing Act of 1937 led to the construction of America’s first public housing; a plan further expanded 12 years later. Programs to house the less fortunate continued until 1974, when new government policies ended them. Programs aimed at improving the quality and safety of affordable housing ultimately had the opposite effect, reducing the number of units available. Additionally, the 1980s saw mass closings of mental health facilities, pushing many of their residents to the streets and putting extra strain on an already weak system.

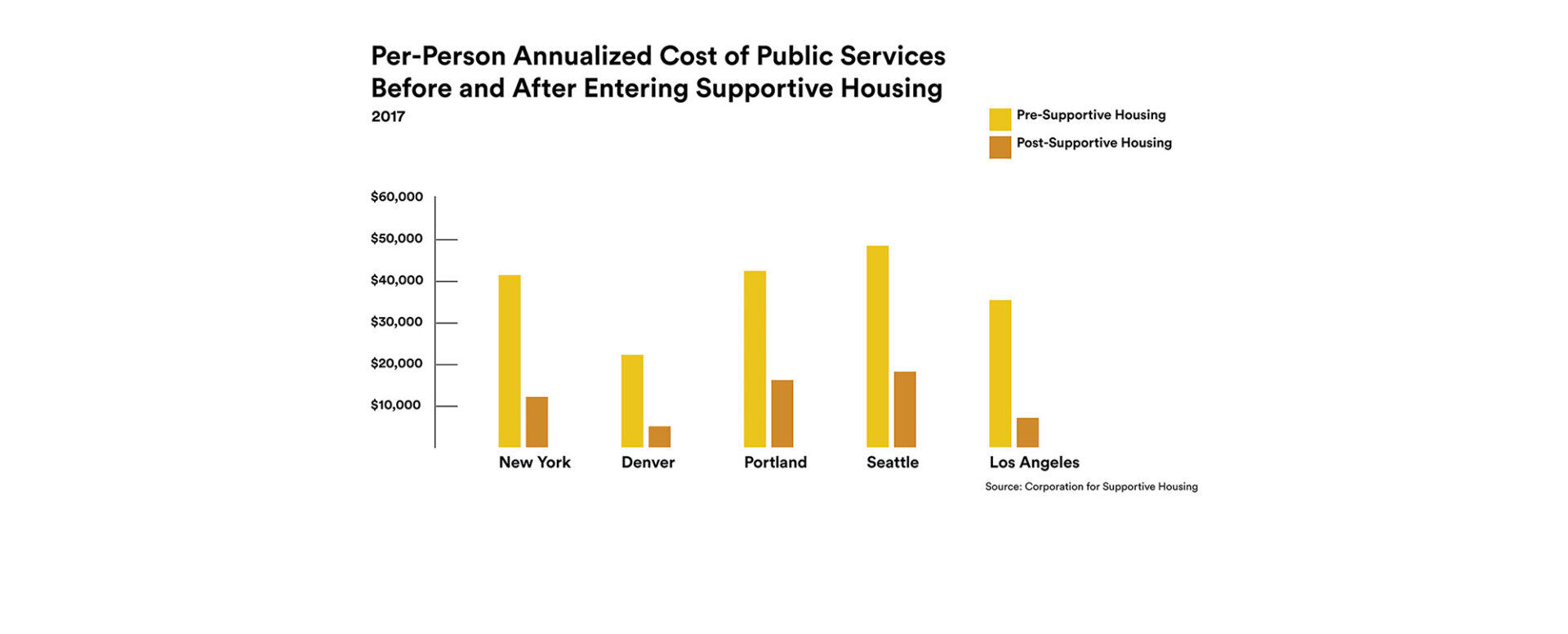

Although the cost of housing America’s unhoused population may seem like an overwhelming drain on taxpayer money, the expense of emergency services for individuals living on the streets ultimately exceeds the cost of subsidized housing. When formerly unhoused individuals can settle into long-term housing, they experience improvements in their mental and physical health and increased employment opportunities leading to future stability and success.

The City of Los Angeles’ 2016 Proposition HHH Supportive Housing Loan Program seeks to address creation of new residential construction for unhoused individuals, but to date only 8,091 housing units have been designated HHH funding; meanwhile there are almost 70 thousand people in Los Angeles experiencing homelessness on any given night.

Skid Row

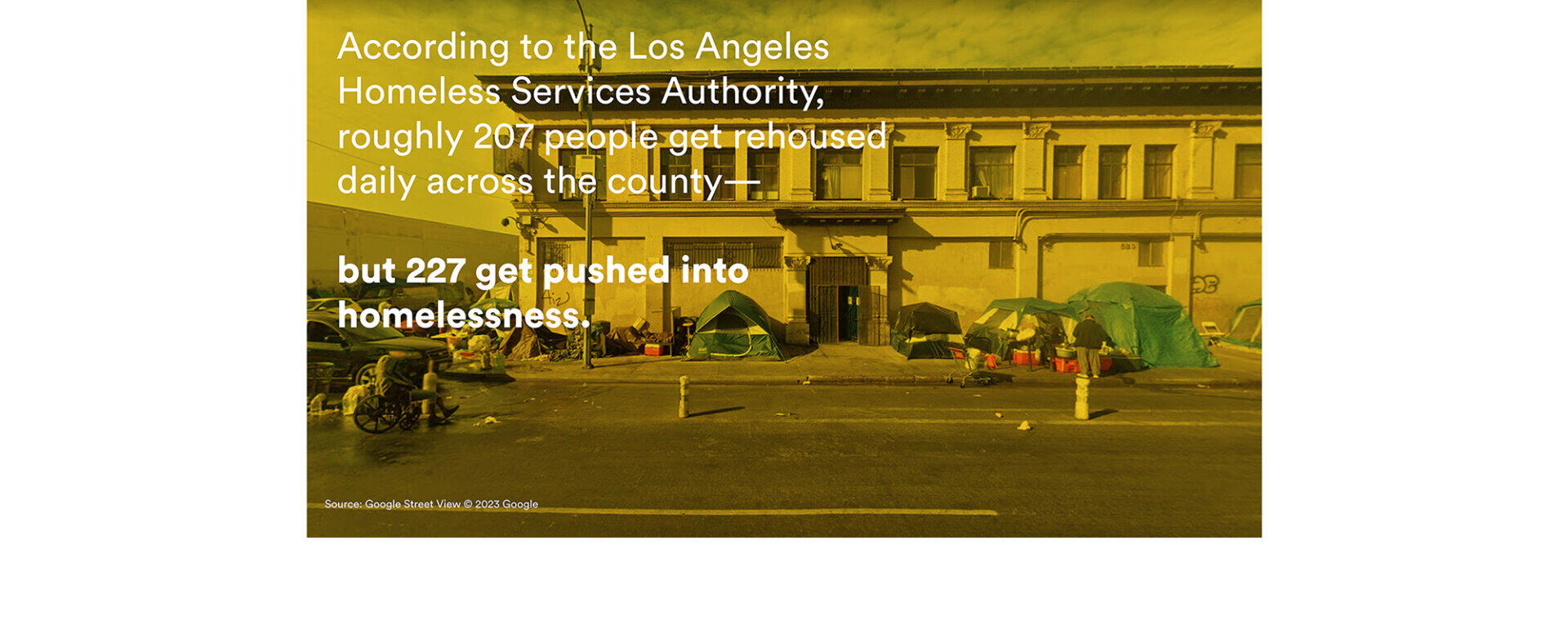

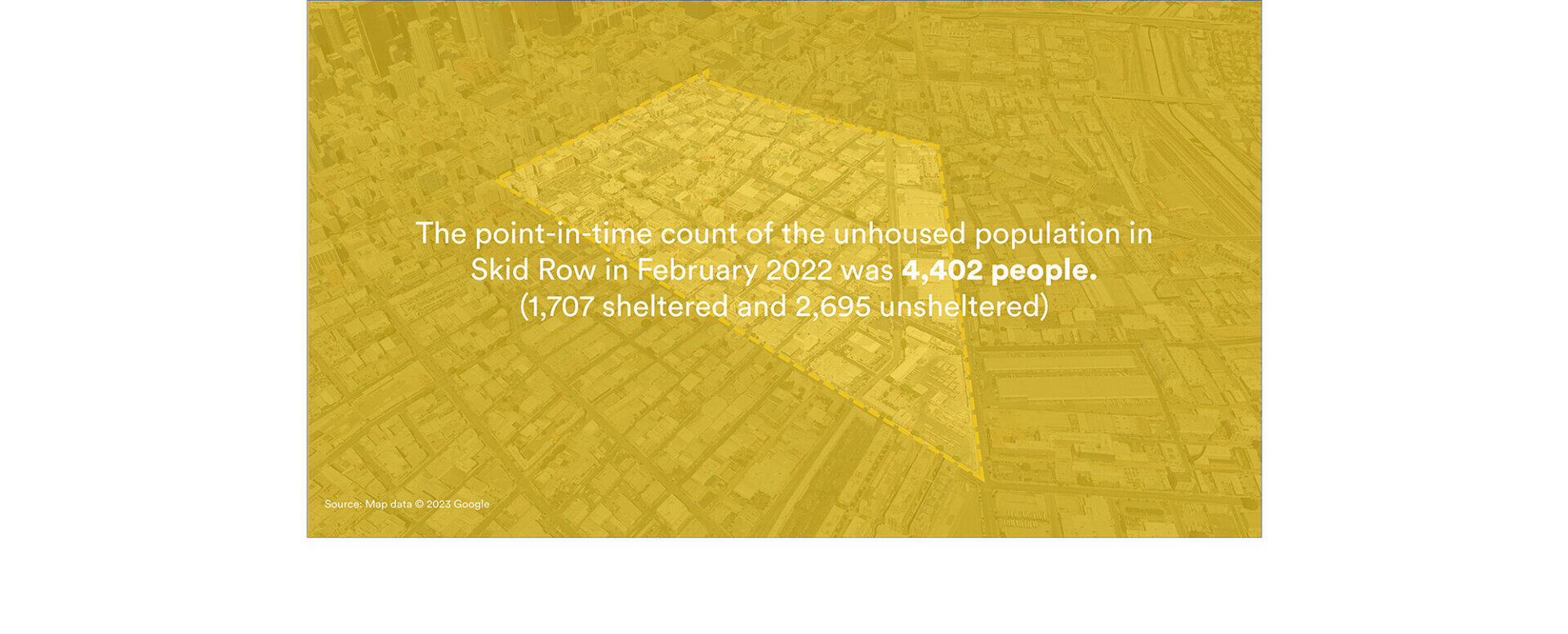

The point-in-time count of the unhoused population in Skid Row in February 2022 was 4,402 people (1,707 sheltered and 2,695 unsheltered). Also known as Central City East, the 50-square-blocks of Skid Row have long been home to Los Angelenos with the least. Named for the “skid roads” built to transport logs along muddy streets, Skid Row saw an influx of transient, immigrant men arrive in Los Angeles during the mid-19th century. They looked for work building the railroads and spent their earnings on prostitution and liquor. Bars, brothels, and single-room-occupancy units (SROs) popped up to accommodate the new demand. The Great Depression brought a further influx of single men looking for work to Southern California, but the available work was often seasonal and scarce. As rampant alcoholism and seedy behavior dominated the Skid Row community, local church groups responded by providing food and services through a series of religious missions. By the 1950s, many SRO buildings fell into disrepair and as the city attempted to increase safety code enforcement, many owners couldn’t afford costly updates and instead chose to demolish their buildings. Rather than address the deterioration of the urban core, suburban sprawl drew residents away from the city, further burdening commercial interests. In recent years, new initiatives, such as Los Angeles’ 2016 Proposition HHH Supportive Loan Housing Program, have strived to revitalize Downtown Los Angeles and spur development of affordable housing within the urban core. Even with a renewed sense of priority, the necessary development can’t happen fast enough. While services in Los Angeles County successfully rehouse roughly 207 homeless individuals every day, simultaneously, another 227 are driven into homelessness.

Source: Corporation for Supportive Housing

Source: Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority

Source: Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority

A Big Solution for A Big Problem

KTGY has been privileged to design many communities providing supportive housing for formerly unhoused individuals. Understandably, supportive housing is a sensitive topic that begs the question, how do we balance providing as many homes as possible in a reasonable and respectful way?

KTGY’s typical supportive housing development includes small studio units for each resident, with a private kitchen and bathroom. This type of community often experiences extended timelines due to increased public scrutiny. For example, KTGY’s Hope on Alvarado in Los Angeles provided housing for 84 unhoused individuals, taking nearly four years to complete, from initial design studies to resident move-in. Subsequent similar steel modular projects experienced a streamlined construction process, benefitting from the lessons learned.

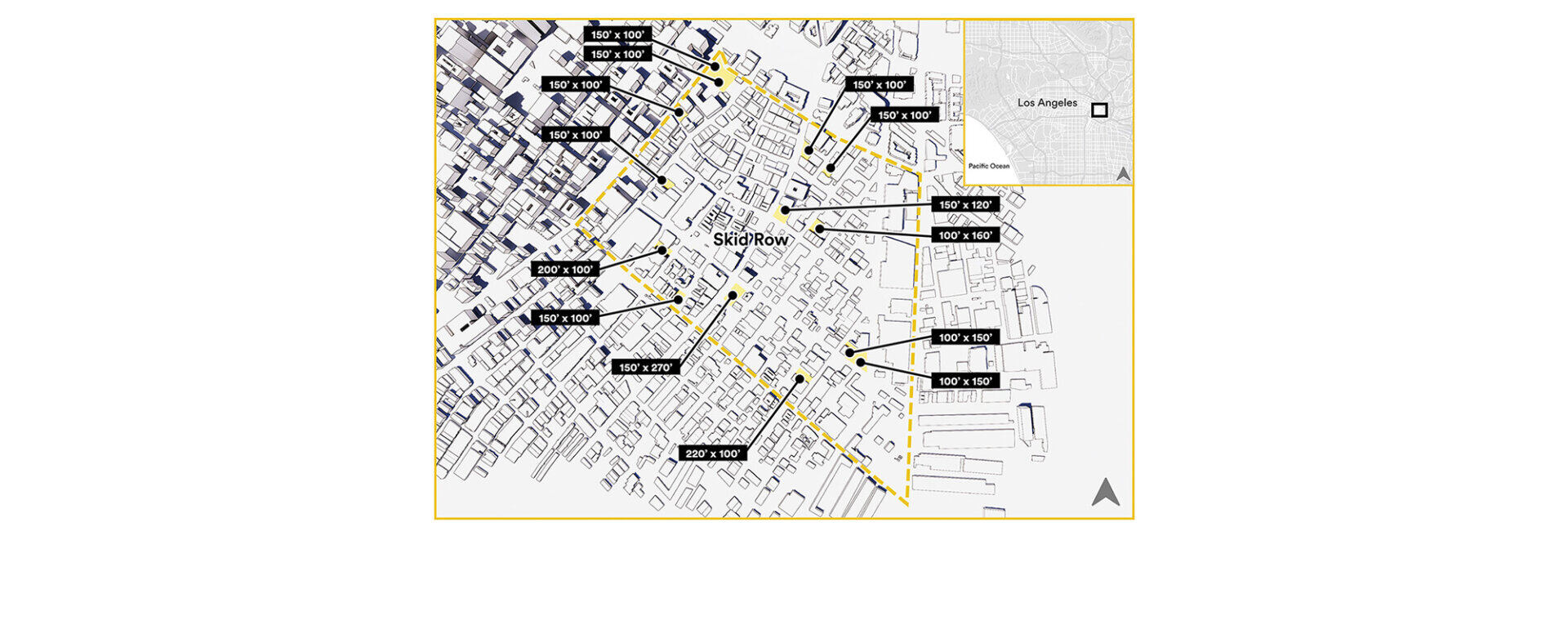

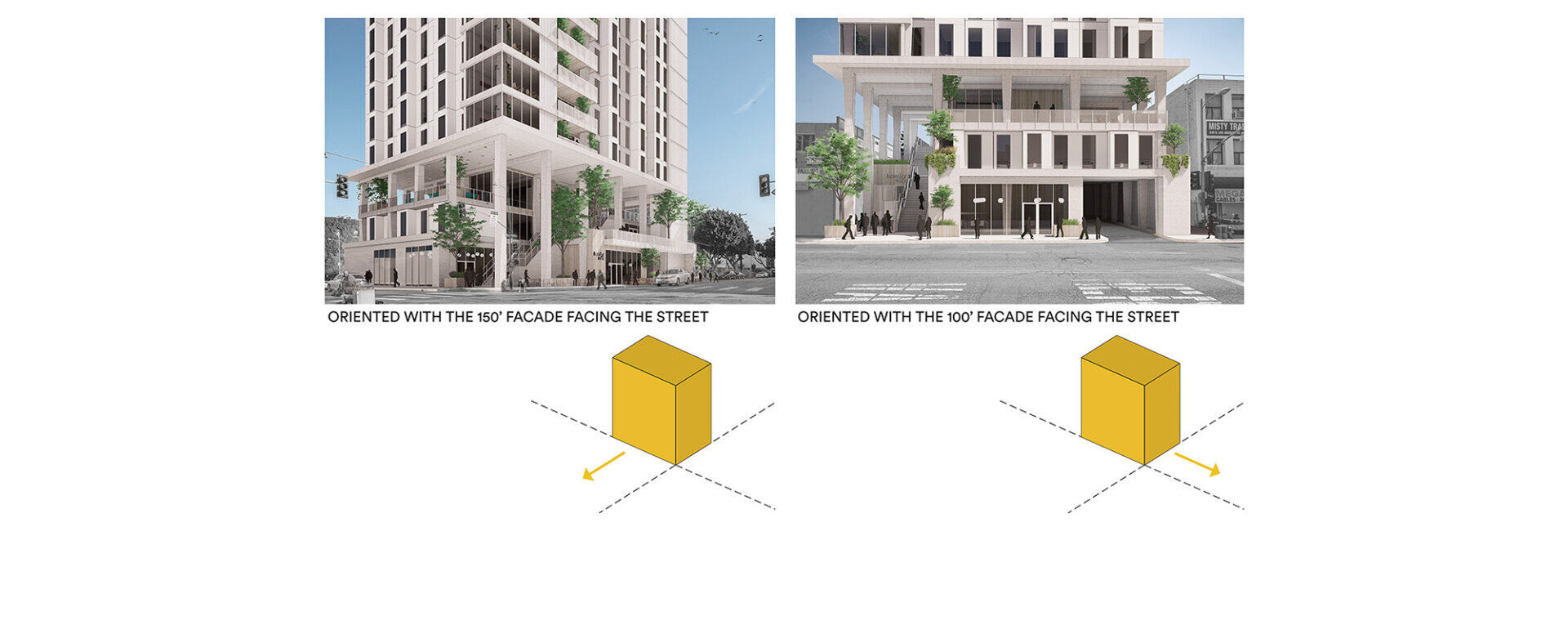

Expanding on the idea of efficiency in repetition and in response to Los Angeles’ ongoing and growing challenge of housing its massive, unhoused population, KTGY’s Research and Development Studio designed The Essential, a concept proposing a prototypical 12-story concrete building with steel modular units, housing 335 people and providing essential support services. Fitting within a 100-foot-by-150-foot site, The Essential is designed to flexibly accommodate up to 14 different, underutilized sites within the Skid Row neighborhood, providing housing and services to the unhoused.

A Big Solution for a Big Problem | A modest, approachable design for this 12-story supportive housing building quickly provides 335 beds.

A Big Solution for a Big Problem | Fitting within a 100′ x 150′ site, The Essential can flexibly accommodate up to 14 different underutilized sites within Skid Row.

A Big Solution for a Big Problem | The Essential proposes a repeatable neighborhood-scale design solution for housing the unhoused population.

Standardized + Easily Repeatable Design | Modular construction on upper levels helps streamline the process and reduce timelines.

Standardized + Easily Repeatable Design | While upper levels remain identical, the ground level has a flexible design to accommodate multiple site configurations.

Standardized + Easily Repeatable Design | The lower levels are designed to be integrated with the surrounding community and provide much-needed services.

Meeting People Where They Are

Some communities have responded to the need to house the unhoused by relocating individuals to adjacent communities, deflecting the burden on other neighborhoods and invoking backlash from community members. Rather than relocating these unhoused individuals, The Essential proposes finding underutilized sites in communities experiencing significant homeless populations. While it may seem like unhoused individuals are transient in nature, many feel strong connections to their communities and have lived on the streets within a particular area for an extended period. In addition, services and resources designed to support unhoused individuals are often concentrated in certain areas. By developing housing in proximity, individuals can have easy access to both housing and essential services.

Standardized and Easily Repeatable Design

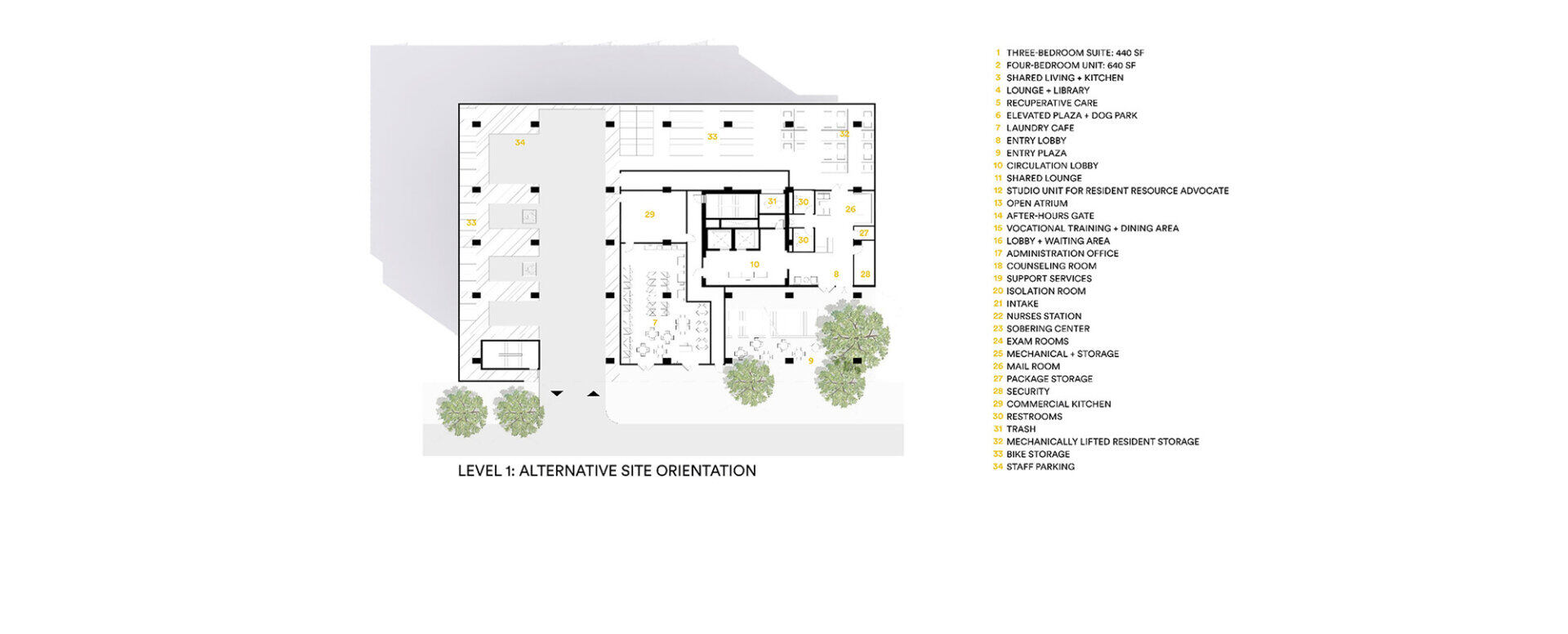

To make a greater impact on the daunting task of housing the unhoused, a standardized and repeatable approach can streamline the process and reduce timelines. Replication can minimize the number of details created, reduce the time spent reviewing drawings, and mitigate future negative feedback by incorporating lessons learned. By combining modular design on the upper levels of the building with a prototype strategy for the building as a whole, The Essential suggests a methodology that can generate a larger number of homes in a shorter period of time. While the upper levels remain identical from site to site, the ground level has a flexible design, which can be used on sites where either the long or short dimension faces the public way.

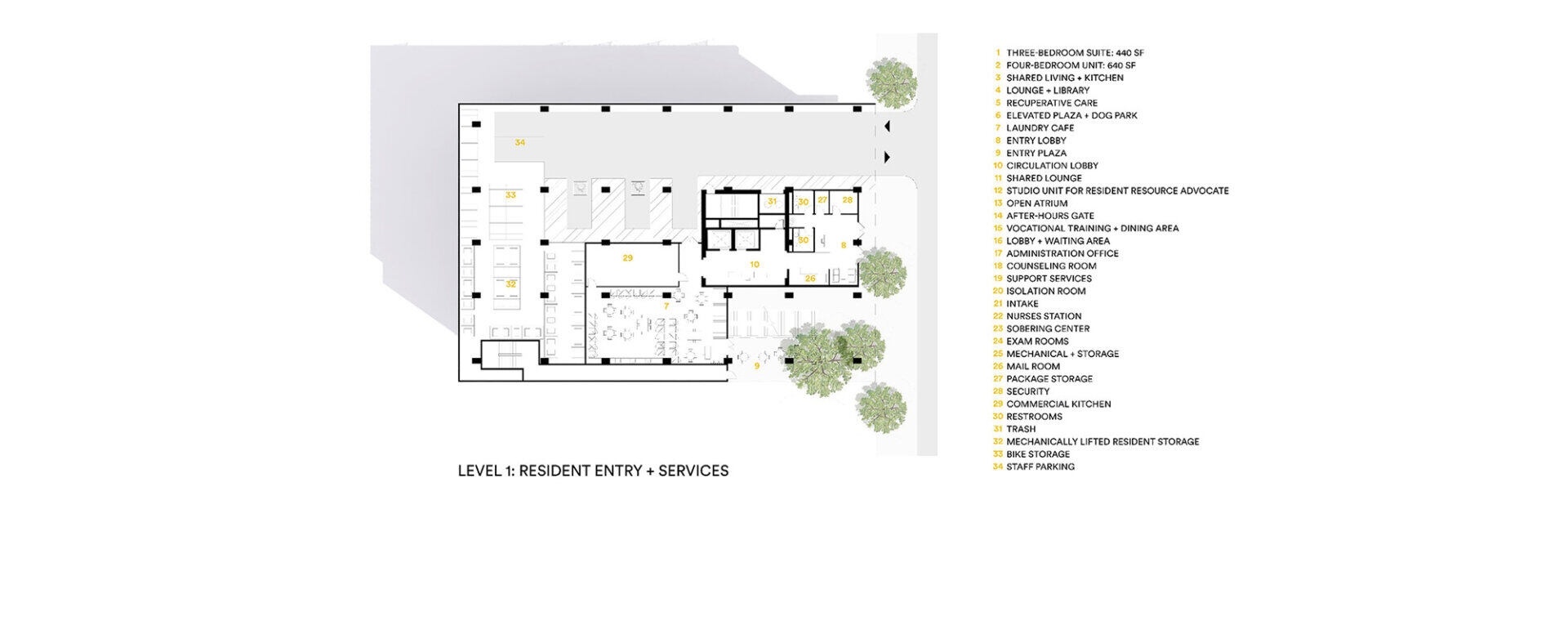

Level 1 Floorplan

Alternative Level 1 Floorplan

Supporting the Community | A ground-floor laundry café serves residents + neighborhood.

Supporting the Community | The lobby welcomes residents and visitors and provides a gathering space.

Supporting the Community | A public ground-level plaza incorporates seating, bike parking, and serves as interface between public and private spaces.

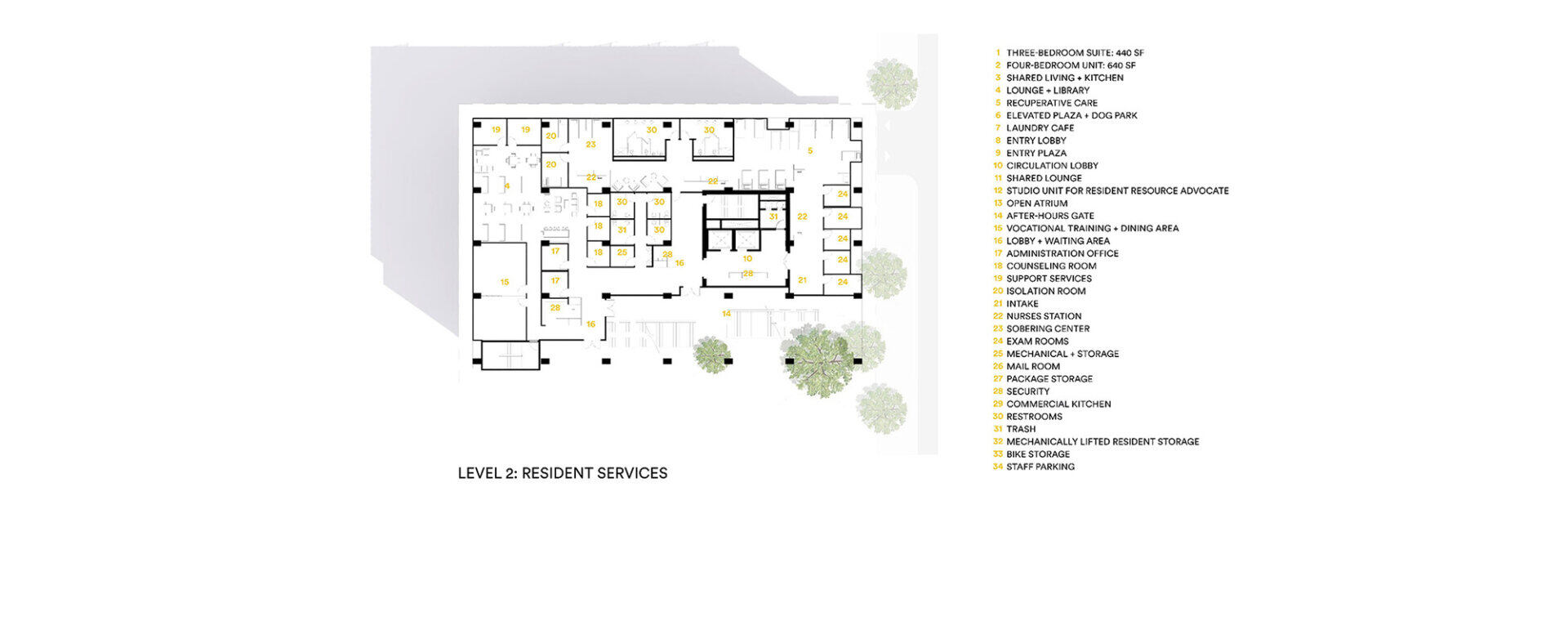

Level 2 Floorplan

Supporting the Community | Second floor library and lounge sits within the services center which includes counseling and job training.

Supporting the Community | The recuperative care and sobering center houses nurses stations, 14 patient beds, exam rooms, and isolation rooms.

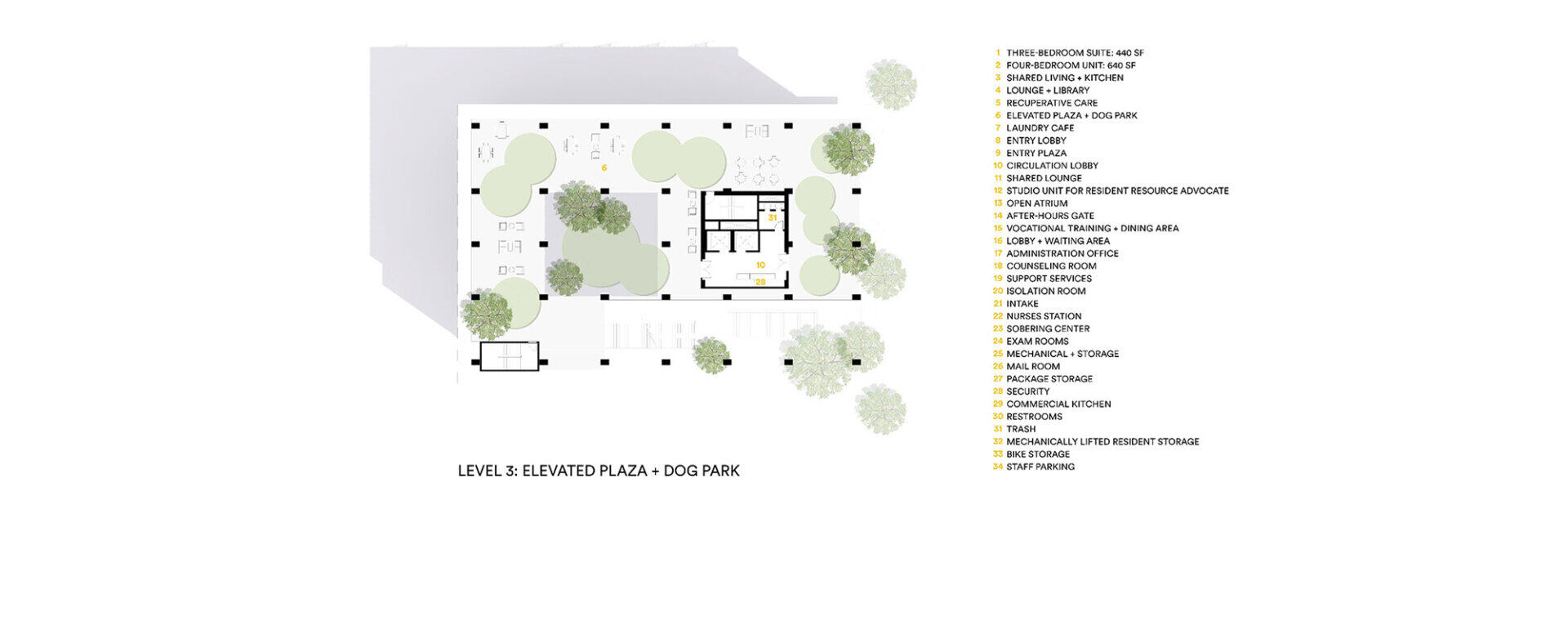

Level 3 Floorplan

Supporting the Community | An elevated plaza at the third level offers a place for residents to relax and care for their pets.

Supporting the Community

The Essential strives to be a support system and community resource. A ground-level plaza serves as an interface between public and private spaces with seating, bike parking, and greenery. A large lobby welcomes new residents and houses a mail room and resident storage areas. The laundry café serves the community while also providing job training and work opportunities for residents. On level two, resident support services include counseling, training, administrative services, recuperative care, and a sobering center. The recuperative care and sobering center include nurses’ stations, 14 patient beds, exam rooms, and isolation rooms. At level three, an elevated plaza offers residents a space to relax and care for their pets. Additionally, the shared spaces on levels one through three provide a safe place for residents to spend time during the day.

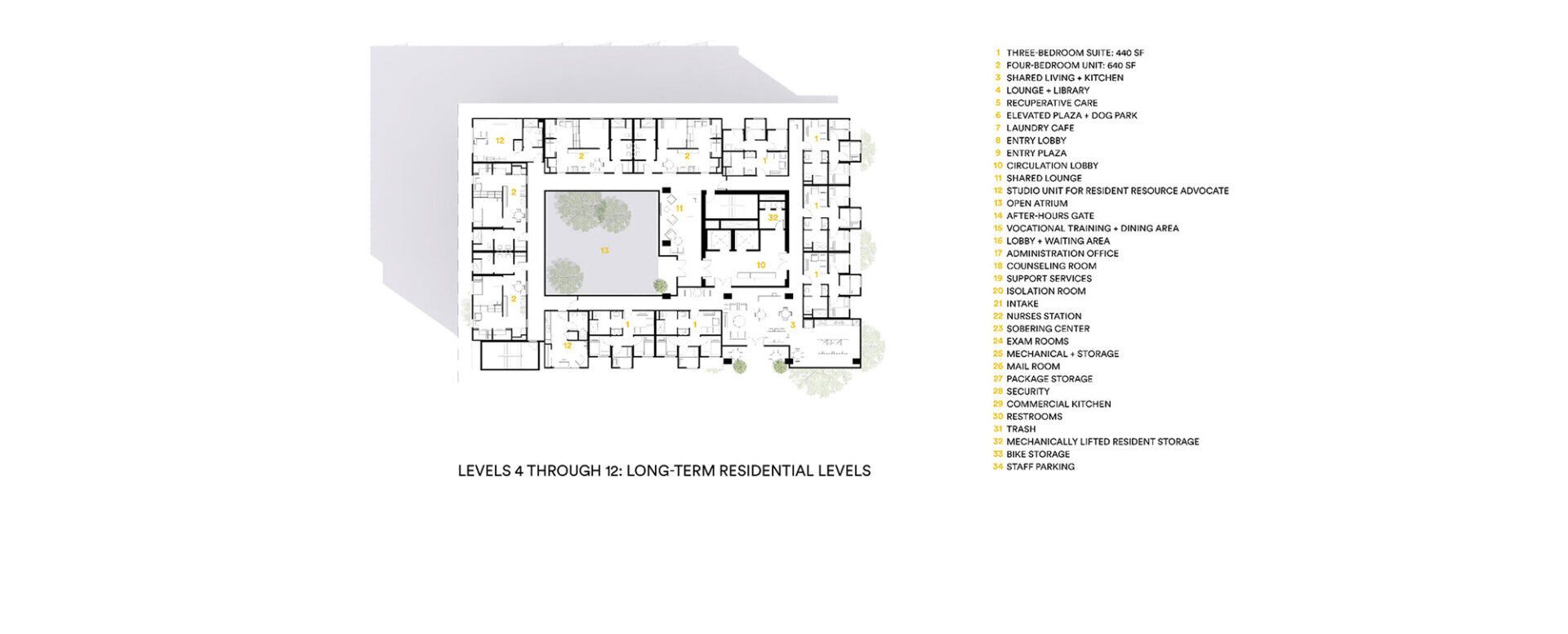

Levels 4 through 12 Floorplan

Supporting the Individual | A large, single unit with six three-bedroom suites shares an over-sized kitchen, dining, and living area.

Supporting the Individual | Suites within the large unit offer a level of privacy but also share a small seating area and bathroom.

Supporting the Individual | Four-bed units on the other wing provide varying levels of privacy for roommates.

Supporting the Individual

On one wing of each residential level, four units house four residents per unit. With sliding doors and multiple configurations, this unit creates levels of privacy and can house singles or couples. On the other wing of the floor, a large, single unit contains six three-bedroom suites. Each suite includes three private bedrooms with a small common seating area and a shared bathroom. The suites also share an oversized kitchen, dining, and living area. On each residential level, resident advocates are available for support, as needed.

Where else could The Essential be beneficial?

In response to Los Angeles’ ongoing and growing challenge of housing its massive, unhoused population, KTGY’s R+D Studio designed The Essential, a 12-story housing concept integrating social services and shared living to support the wellbeing and success of unhoused individuals. The Essential aims to spark a conversation about the homelessness crisis facing so many American cities. What other neighborhoods beyond Skid Row could benefit from this concept?

Map of Denver, CO

Map of San Francisco, CA

Map of Chicago, IL

Map of Washington, D.C.