Suburban sprawl boomed starting in the 1950s with the expansion of the US Interstate Highway System and the effects of the GI Bill. Rates of private vehicle ownership rose sharply, with cheap gas and stagnant mass transit systems further encouraging the use of cars. However, more recent expansion of mass transit systems, a clearer understanding of the environmental impacts of cars, and new alternatives to daily driving, such as ride-share apps, bicycle-share companies, and the prevalence of remote work, have led Americans to slowly reduce their dependence on cars.

This car dependence has influenced development policy over the decades. Today, there are over two billion parking spaces in the United States, more than enough to cover the entire surface of Connecticut. A 2022 driving habits survey by U.S. News and World Report World Report found that nearly half of drivers have reduced their driving compared to pre-pandemic levels, and over 60 percent have curtailed their driving due to higher gas prices. Interestingly, the youngest generation of drivers is obtaining licenses at a slower rate than any previous generation.

Municipalities have noticed these shifts and responded by beginning to eliminate parking minimums for new development in transit-oriented communities. In 2017, the city of Buffalo, New York, was the first in the United States to abandon parking minimums.

Since then, other cities have followed their lead: from Santa Monica, California to Hartford, Connecticut.

These shifts in driving habits expose the latent possibility for more efficient and less expensive new development. According to construction engineering firm, WGI, building a new parking structure costs nearly $28,000 per space. Outdated parking minimum requirements can impose significant expenses, hindering new residential development and worsening existing housing shortages.

Eliminating previously built parking structures will have its own negative impact. The waste generated by demolition and subsequent new construction makes adaptive reuse an attractive alternative. By converting a parking structure to housing, waste is minimized and embodied carbon is reduced.

A few years ago, KTGY’s Research and Development Studio proposed a design concept for repurposing underutilized parking structures for housing. Starting with an existing parking structure from a completed wrap building in San Diego, California, we reimagined the donut-shaped, standalone structure, inserting factory-built steel modules to create a new housing concept: Park House. The proposed Park House design repurposed 1,091 parking spaces to achieve 119 one- and two-bedroom units.

Developing the Park House concept taught us some important things:

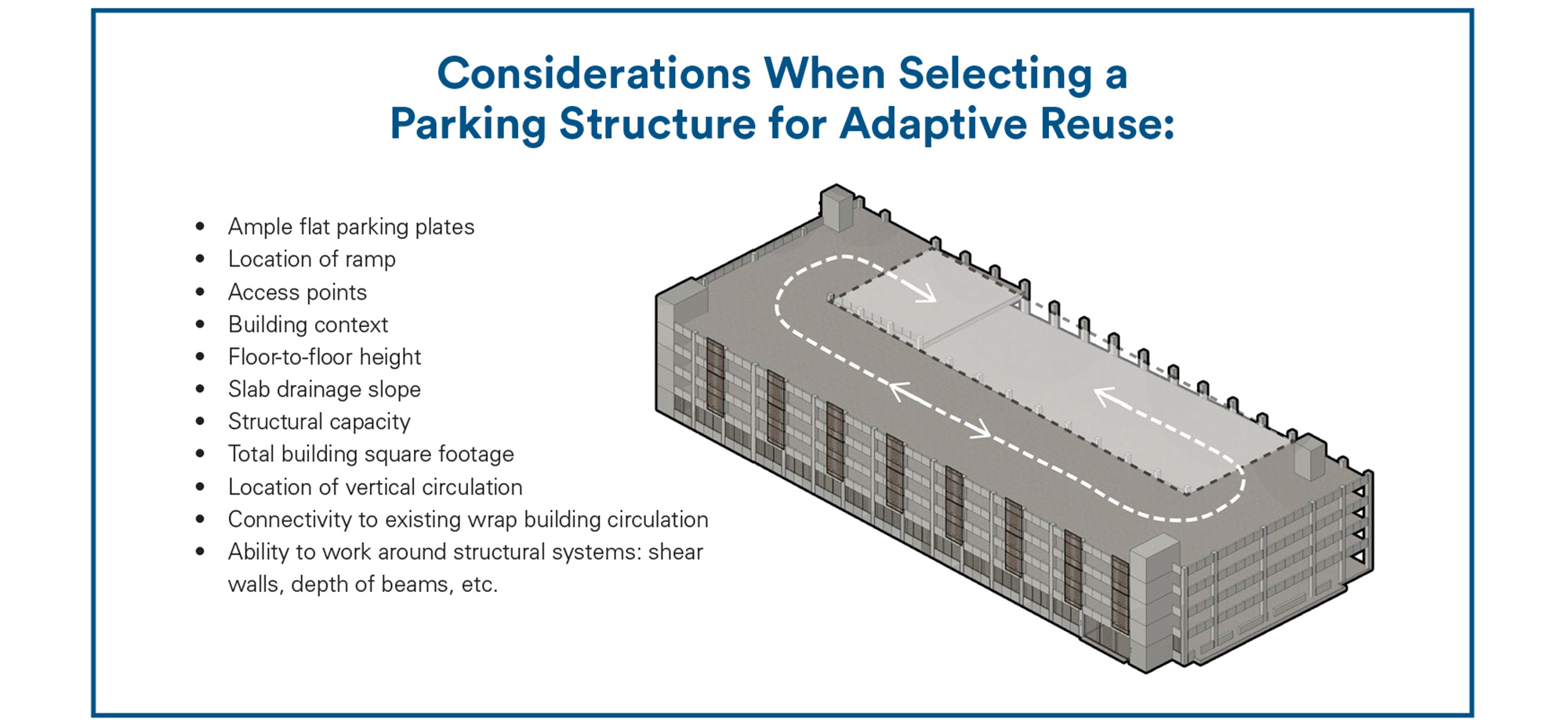

1. To effectively adapt a parking garage for residential, large portions of the parking structure must be flat (or very close to flat).

2. Working around the ramp presents a challenge, but its central location makes it a natural fit for the community courtyard space.

3. Distance between floors should be maximized, allowing for at least seven feet of clear height within the units.

Other considerations when studying the potential transformation of a preexisting parking structure include: intrusion into interior clearance height, structural capacity, total building square footage, stair and elevator locations, site access points, and proximity to adjacent buildings. While not critical, a wide column grid allows larger, unobstructed unit areas. Additionally, it’s important to note that local building height limits may restrict the ability to construct units on the top level of the parking structure.

We also learned that transforming an entire parking structure to residential is a dramatic undertaking, and one that many multifamily developments won’t fully commit to all at once. Consider a parking structure where just half the floors are consistently empty — or only a single floor — adapting the entire structure would be unreasonable. A smaller, incremental transformation, however, provides flexibility and reduced overhead, enabling building owners to respond to the needs of residents while adding value to underutilized spaces, all within existing capacity.

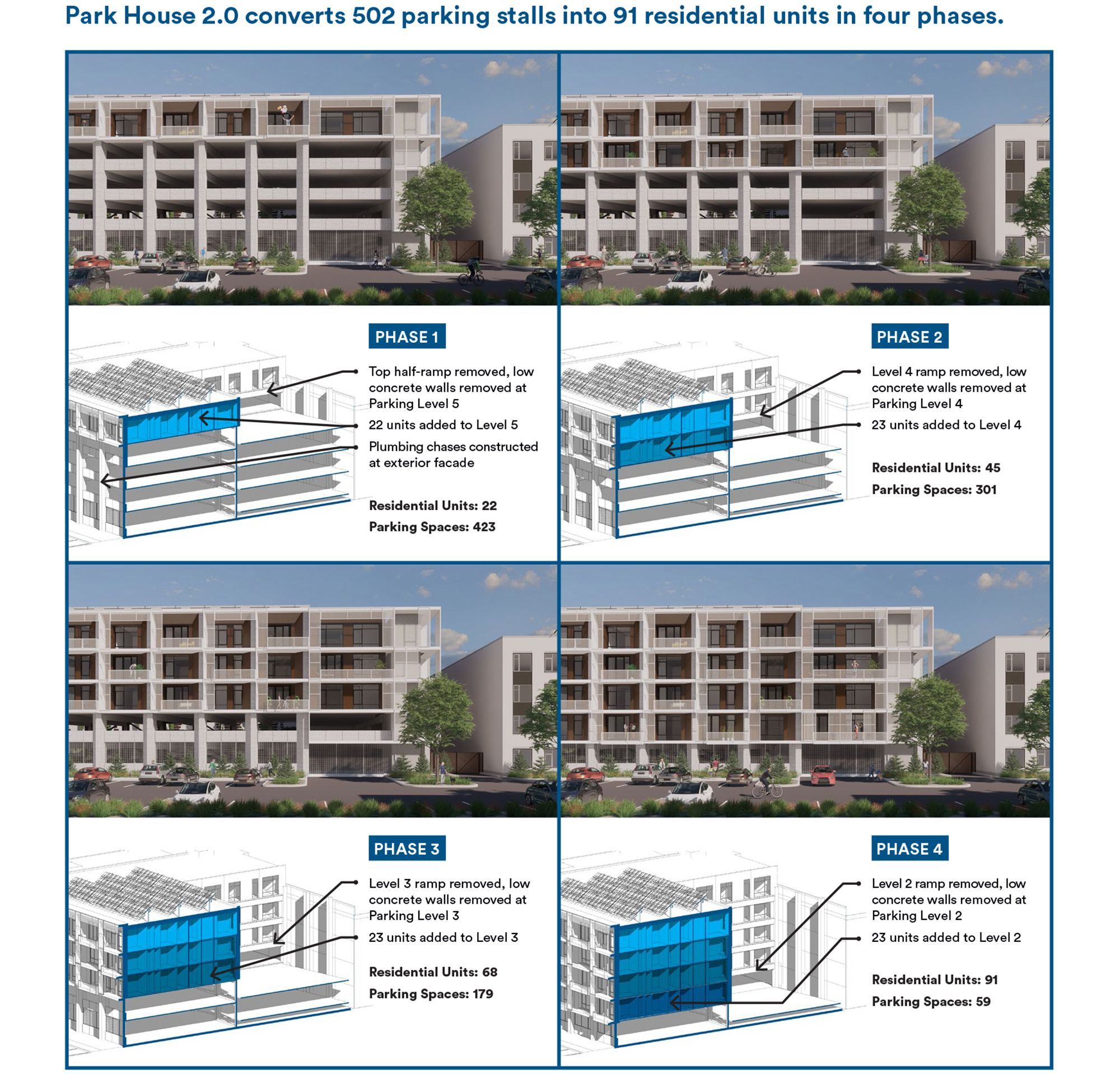

Using the 561-space parking structure from a KTGY-designed wrap building located in San Jose, California, as a case study, the Research and Development Studio reimagined how a parking structure could be modified incrementally, creating a phased approach to this adaptive reuse solution.

To prepare the concrete parking structure for transformation, first a short extension at the highest portion of the ramp is removed and the shear wall adjacent to the ramp is replaced with brace frames and moment frames. This allows for the future addition of units in

those areas.

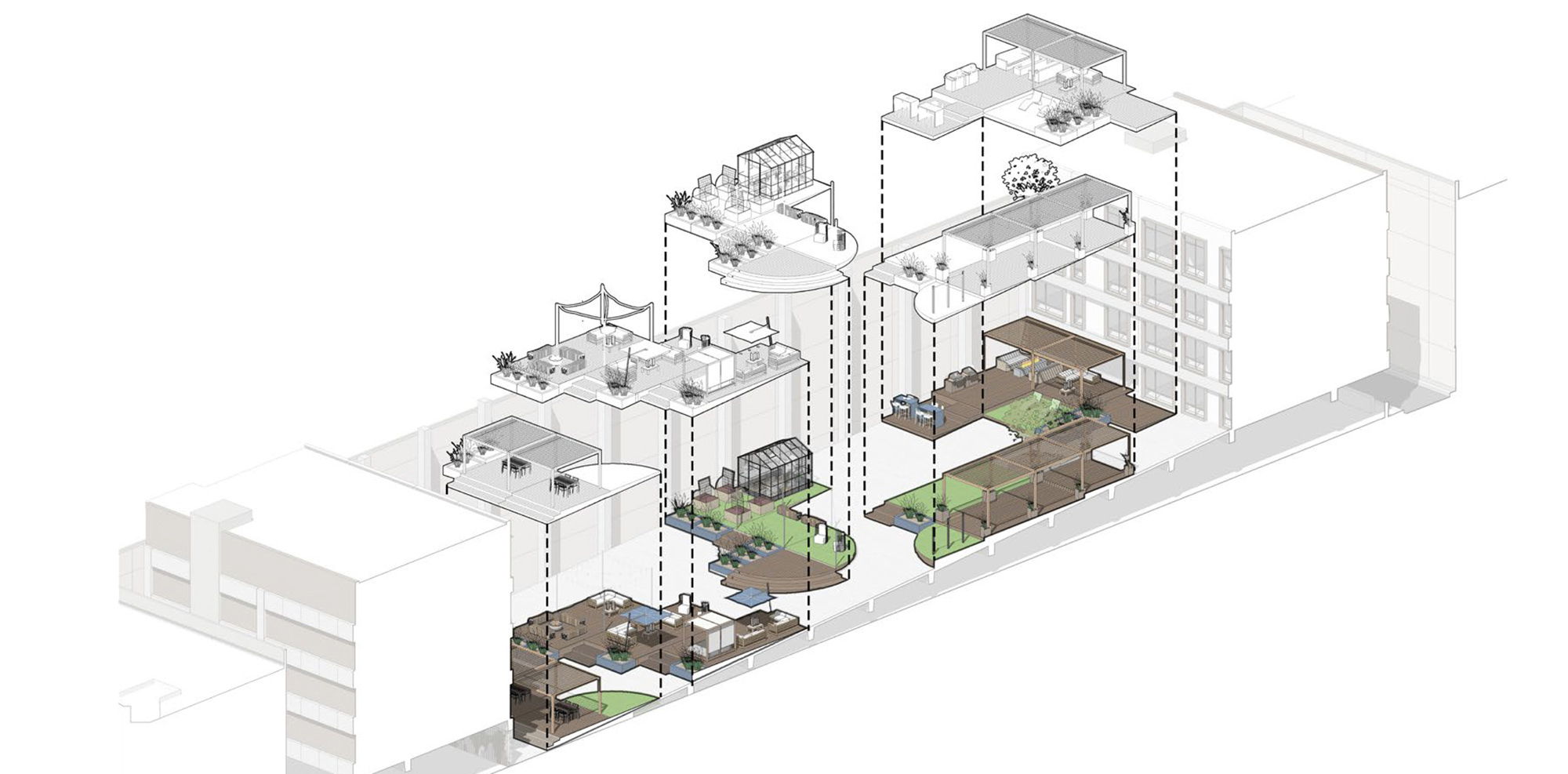

The initial addition of units begins with the highest level of the garage. Twenty-two units are added in phase one, repurposing 138 parking spaces. A sloped amenity ramp and utility chases running vertically along the exterior of the building are also added during the first phase of construction. During the second phase of construction, the top level of the ramp is removed, shifting the amenity courtyard to the ramp below.

Subsequent phases follow a similar pattern. A level of the ramp is removed, shifting the amenity space down. Units are inserted on the next highest level, replacing that level of parking spaces.

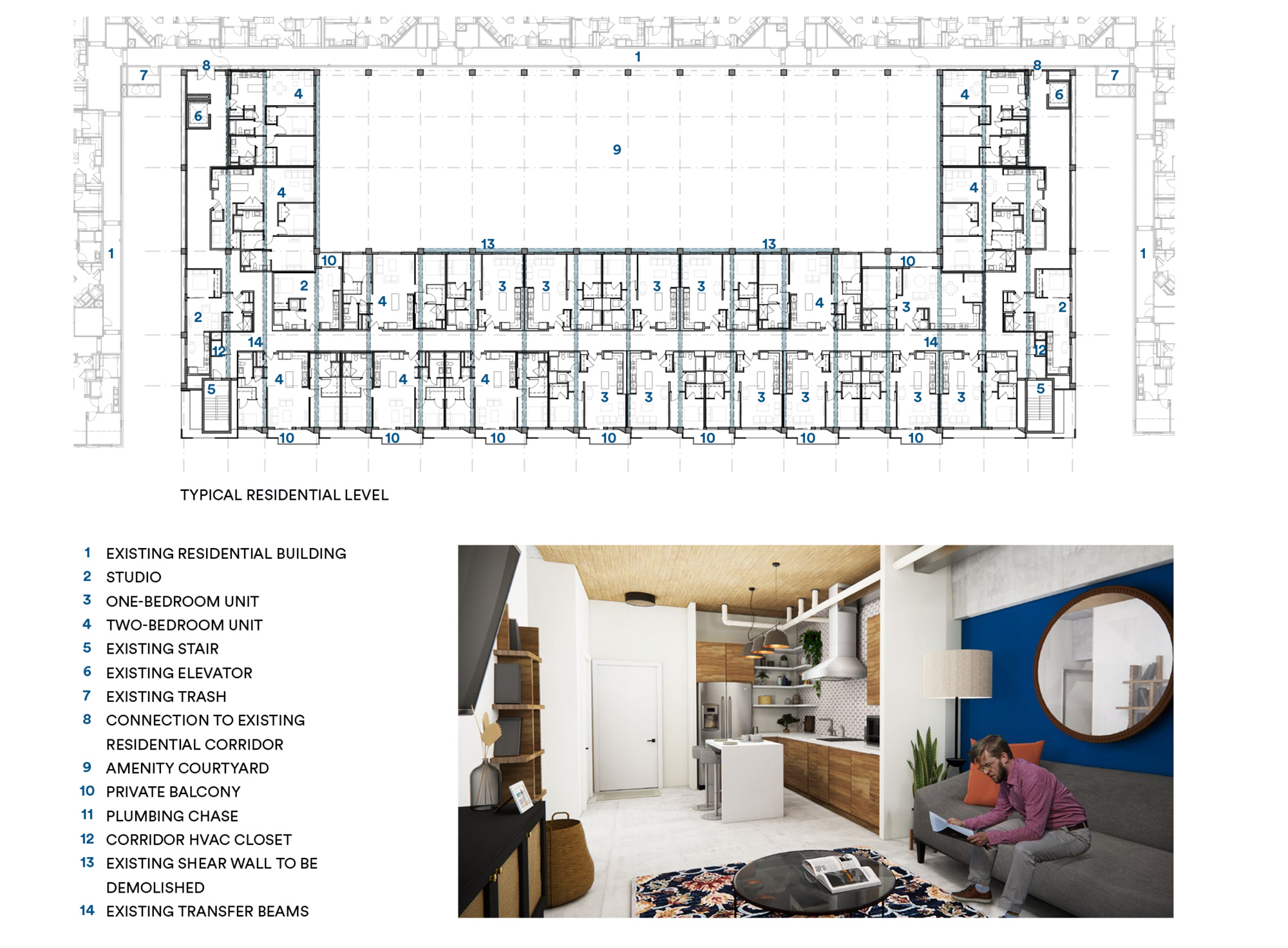

With all four phases of the transformation complete, the Park House 2.0 design proposes 91 units on four floors of the five-story parking structure, with 59 parking spaces remaining at the ground level.

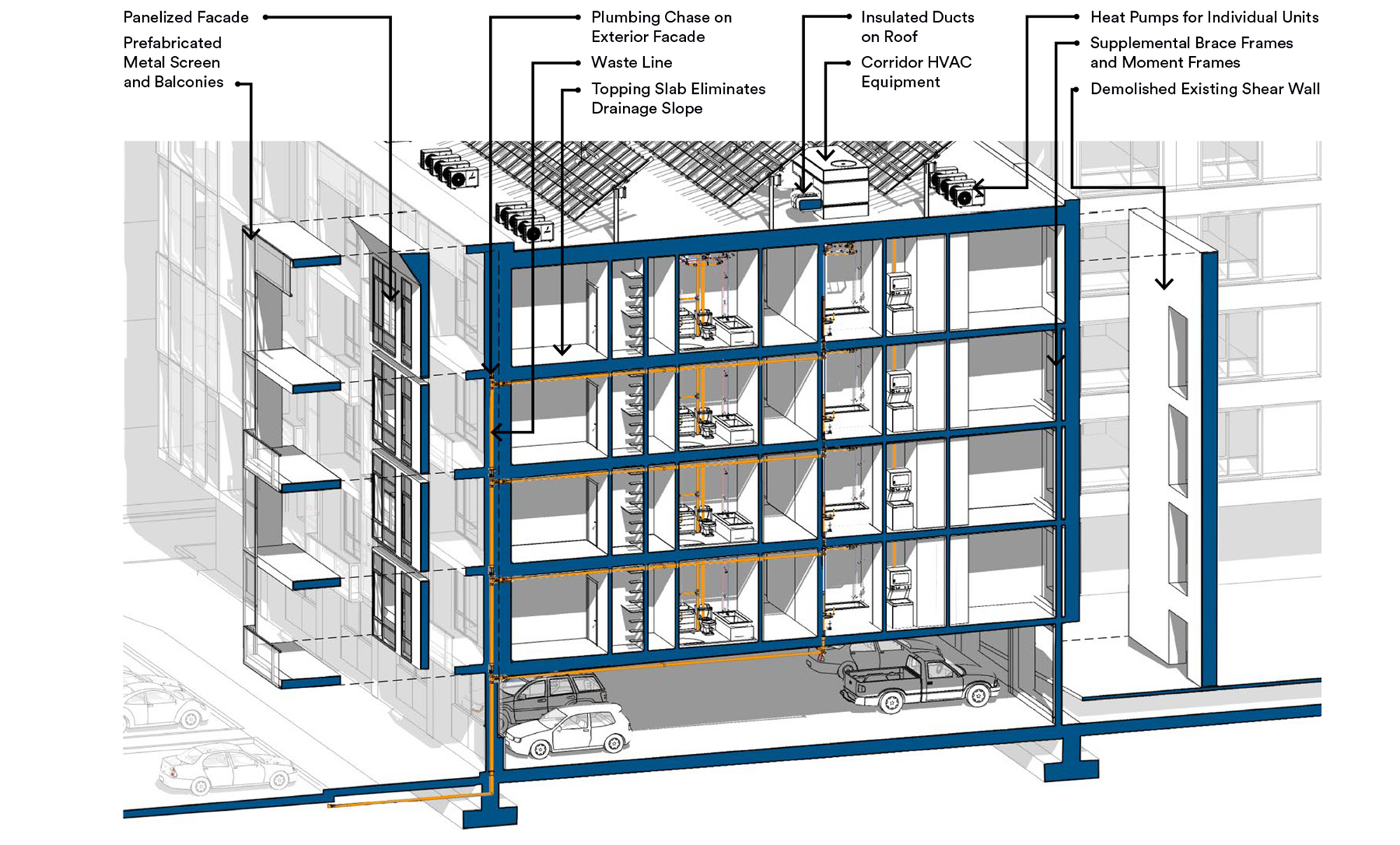

The shear wall adjacent to the ramp is replaced with brace frames and moment frames. This design allows for the future addition of units in those areas. Brace frames are used where the entire frame will fit within a single unit, while moment frames are used where the frame will cross between two adjacent units.

Pipes servicing the units run toward the exterior of the building, traversing down through vertical chases running along the façade. All plumbing and utilities run within the existing structural bays to avoid routing beneath deep transfer beams and compromising clear heights within the units. Heat pump refrigerant lines also run within these vertical chases to route from rooftop heat pumps to individual units. As units are added in future phases, plumbing and mechanical systems join with the vertical chases placed during the first phase of construction.

To maintain a one-hour separation between the different occupancy types of parking (S-2) and residential (R-2) during each phase, a topping slab is added to the parking plate. This maintains a level floor surface and creates the necessary concrete thickness for a one-hour separation.

KTGY’s R+D concept, Park House 2.0, looks to reimagine parking structures through a phased and incremental approach. This strategy empowers building owners to adapt their developments to evolving resident needs, capturing value in underutilized spaces. Predicting how Americans will modify their driving habits in the future is challenging, but an incremental approach facilitates swift adjustment to these changes.